The recently completed 2020 MLB season was mostly notable for its upheavals and uncertainties. Now that the season is done, the temptation for observers is to assume that normality will return to the sport in 2021. Unfortunately, that's probably not going to be the case for a number of reasons -- many of them owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.

With that in mind, let's have a quick walking tour of how the turbulence of the 2020 season will continue to inform baseball's near- to mid-term future.

The new rules

The 2020 season famously/infamously featured a number of rule changes, many of the drastic variety. Two of those changes -- the minimum three-batter rule for relievers and the expansion of the active roster to 26 players -- are permanent. Others, like the designated hitter in the National League, having a runner start on second base in extra innings, shortening doubleheader games to seven innings, and the expanded playoffs may not return next season.

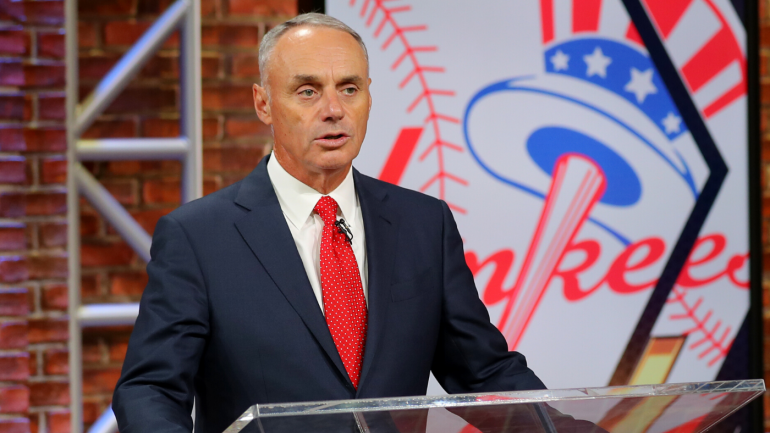

But what about once the next collective bargaining agreement is instituted? Might the next agreement between players and owners implement some of these controversial changes to the game on a permanent basis? Signs point to probably. Commissioner Rob Manfred recently said this to the Associated Press about those rule changes:

"People were wildly unenthusiastic about the changes. And then when they saw them in action, they were much more positive."

In particular, Manfred would like to see the playoffs permanently expanded -- albeit probably to 14 teams instead of the 16-team format of 2020 -- and for the runner-on-second rule for extra innings to stick around. Players might need to be persuaded on the first count, but they'll almost certainly support anything that makes 15-inning games less likely.

As well, there was already some pre-2020 momentum to install the DH in the NL, and that's very likely an easy sell to players. The 2020 season served as a way to acclimate fans to the idea of never seeing pitchers hit, and the initial outcry against it seemed to peter out fairly quickly. Beyond all that, Manfred has once again hinted at the possibility of banning infield shifts.

For better or ill, Manfred has been bold in pursuing structural tweaks to the sport, and there's no reason to think that will change. The guess here is that by the time the 2022 season arrives, the DH is a permanent presence in the NL, and every inning from the 10th onward begins with a runner on second base.

The restructuring of the minor leagues

Thanks to the pandemic, Minor League Baseball (MiLB) for the first time in its 120-year history did not play a season. Unfortunately, the trouble down on the farm don't end there.

For a while now, MLB has had designs on whittling down the affiliated minor leagues -- i.e., those farm teams formally linked to an MLB organization. The working agreement between MLB and MiLB has already expired, and MLB will largely wind up getting its way via whatever comes next, whether it be a new agreement or MLB dissolving ties completely and establishing its own developmental framework. MLB will reduce the number of farm teams to 120 or so, which means more than 40 minor league teams will lose affiliate status. In related matters, former rookie leagues will likely be converted into summer wood bat leagues for college players.

Starting 2021, the minor leagues will be more uniform in terms of the quality of facilities, and players will be slightly better compensated. However, there will fewer affiliated teams and as such fewer affiliated prospects.

The looming labor war

The current collective bargaining agreement (CBA), which is the negotiated agreement that governs almost every aspect of the working relationship between management (the clubs) and labor (the players), is set to expire after the 2021 season. While we've had a historic run of labor peace in baseball -- no labor stoppages since 1995 -- there's reason for pessimism in the here and now.

The talks leading up to the 2020 campaign, which because of the COVID-19 pandemic required one-off negotiations on an array of matters, were more fraught than usual, almost to the point of snuffing out the season altogether. Pursuant to all of it is that, as Evan Drellich recently noted in The Athletic, the players are expected to file a grievance over the owners' bargaining tactics during the run-up to the 2020 season. That could result in a judgement of hundreds of millions of dollars against ownership, and that in turn could lead to further financial retrenchment on the part of management.

That's on top of the already percolating tensions between the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) and owners on the matter of player compensation. Said tensions were in play during the last CBA negotiations in 2016, when an agreement wasn't forged until the final day before the deadline. That agreement tabled rather than resolved the economic conflicts facing the game.

From the players' standpoint, in the upcoming talks they'd surely like to address their shrinking share of league revenues, the practice of service time manipulation (i.e., when teams hold back a clearly ready prospect in order to delay his free agency or arbitration eligibility for a full year), and the practice of "tanking," among other matters. For the owners, the motivations remain the same, even if the particulars have changed -- limiting labor costs as much as possible, even to the detriment of the on-field product. That means the players can expect resistance of every front that has the potential to reduce ownership profits.

Clubs have increasingly come to rely on young talent because young talent is cheaper while often providing similar or even superior production than older, more expensive players. At the same time an inevitable de-emphasis on free agents is providing additional downward pressure on wages. The MLBPA can fight to alter the salary structure so that it provides more just compensation for younger players, which would entail negotiating earlier arbitration and free agency horizons. Achieving that elusive goal, however, would require nothing short of labor war with the league and owners.

Another possible battlefront is the Competitive Balance Tax (CBT), or "luxury tax." The CBT is levied on teams that exceed the payroll threshold, and it's come to function as a soft cap, largely because teams have over-responded to the built-in incentives. The owners aren't going to weaken it given how well it's accomplished the unstated objective, which is to reduce labor costs. The CBT threshold hasn't kept pace with pre-2020 revenue growth in MLB, and the players will no doubt be pressing for a correction.

Those are bold objectives that will require significant give-backs. The problem is that the MLBPA is running out of carrots to dangle, and that's why approving an international draft may be the players' best option for a concession to owners (however cynical it may be to again bargain away the rights and positions of non-members).

The current economic situation within the game is going to exacerbate these negotiations, which were already going to be heavily fraught. Teams without question saw their revenues decline precipitously during the 2020 season because of the shortened schedule and the fact that fans weren't allowed to attend games until the last rounds of the postseason and even then in limited numbers. The latter means almost not ticket, parking, and concession revenues, and that's a blow to the balance sheet. How much of a blow is difficult to say because MLB and almost all of its constituent teams are not publicly traded entities and thus are under no obligation to "show their work" when they make claims about their finances.

MLB has repeatedly claimed losses of more than $3 billion during 2020. Given ownership's long history of lying about all things financial, there's reason to question the veracity of this figure. They lost money, yes, and probably a lot, but the specifics will forever be elusive and probably less than claimed.

Insofar as player-owner tensions are involved, the point is that the league is already laying the foundation for a free agent freeze-out this offseason. That's already a sore spot for players, and it's going to become more of one as premium FAs like J.T. Realmuto, Trevor Bauer, and George Springer likely find the market lacking. Already we're seeing some incredibly miserly decisions on club options for 2021, and the non-tender market figures to be flooded beyond example. All that of that is going to put downward pressure on the free agent market. The union is going to be frustrated by that, and you'll likely hear whispers of collusion once again.

These also don't figure to be a repeatable set of circumstances once we're clear of the pandemic, but the owners are going to use it for all they can. The problem is that it's going to set a sour tone for negotiations. Right now, the guess here is that a labor stoppage of some kind occurs before a new CBA is forged.

The uncertainty of 2021

It's increasingly looking like we won't have a widely distributed COVID-19 vaccine by the time owners and players need to establish a structure for the 2021 season. It's possible spring training won't be able to begin on time, and it's further possible that once again fans will not be permitted to attend games, at least at the outset.

If that's the case, then owners may once again press for a shorter regular season and prorated salaries for players. All of that would necessitate another round of likely quarrelsome negotiations on what the 2021 season will look like.

Much as it is with the virus that's shaped the sport over this past year, uncertainty prevails in baseball as we look forward to whatever's next.

"may" - Google News

November 01, 2020 at 10:17PM

https://ift.tt/2HXijWu

Why the 2020 season may be a sign of things to come for Major League Baseball - CBS Sports

"may" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3foH8qu

https://ift.tt/2zNW3tO

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why the 2020 season may be a sign of things to come for Major League Baseball - CBS Sports"

Post a Comment