Lockdowns enacted during the early days of the pandemic saved millions of lives and prevented tens of millions of infections. But in most places, quarantine measures were never perfectly implemented. While governments have the power to close businesses and other places where people publicly gather, mandates in the U.S. did not prevent citizens from meeting with friends and family at home.

Anecdotally, informal social gatherings such as holiday get-togethers, parties and weddings seem to have played an important role in spreading the virus. But there is no straightforward way to rigorously test this hypothesis on a large scale. A new study published in JAMA Internal Medicine gets around these difficulties by analyzing the correlation between birthdays and COVID-19 infection rates. According to the findings, households that had a recent birthday—and thus a greater likelihood of having thrown a party—in counties with a lot of cases had about a 30 percent higher risk of infection in the following two weeks, compared with households that did not have a birthday. Those celebrating a child’s birthday, the authors found, were at the highest risk of all.

“Everyone in the study was surprised at how big of an increase in risk this 30 percent seemed,” says lead author Christopher Whaley, a health policy researcher at the Rand Corporation, a nonprofit research group based in Santa Monica, Calif. “I think this really speaks to where a lot of infections came from over the last year.”

While a handful of prior studies examined the role that informal gatherings played in novel coronavirus infections, they mostly focused on one-off events, such as a single wedding reception in Maine. Whaley and his colleagues realized that birthdays could be a particularly useful tool for revealing national COVID-19 transmission patterns for a number of reasons, including the fact that every person has one and that they occur throughout the year.

The authors obtained nationally representative data for 2.9 million U.S. households from Castlight Health, a company that helps people navigate the health care system. The data, which spanned the first 10 months of 2020, included family members’ birthdays, as well as any positive COVID-19 test results they received through insurance claims. While the researchers do not know if the people included in their study actually had a birthday party, they hypothesized that birthdays could serve as a proxy for the likelihood that a social gathering took place.

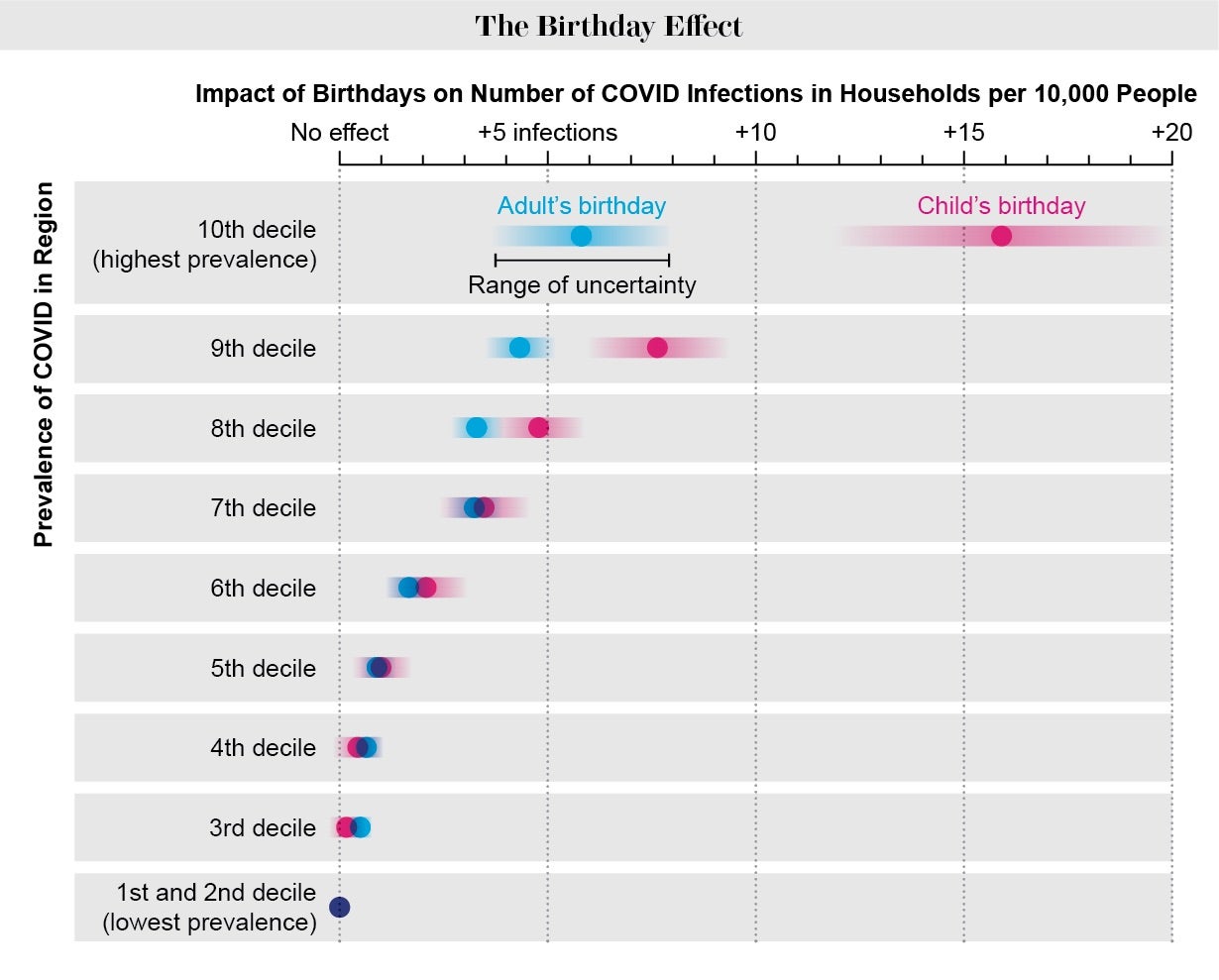

The findings revealed a significant correlation between birthdays and heightened COVID-19 transmission risk. In counties experiencing the highest spread of the disease (the top decile), households with a birthday averaged 8.6 more cases per 10,000 individuals than others nearby without birthdays. In areas with low prevalence of the virus, birthday-correlated infections were also low. Tellingly, the findings were not influenced by political leaning, as measured by how counties voted in the 2016 election. And they were not affected by quarantine orders or the weather. Taken together, this points to a more universal pattern of behavior rather than something that was influenced by extenuating circumstances, such as rain driving a party indoors, or by households’ ideology. “If you’re gathering informally with family and friends, maybe you’re more likely to let your guard down or not wear a mask,” Whaley says. “Psychologically, maybe you don’t think of family and friends as having the same risk level as the general public.”

Whaley and his colleagues were particularly surprised to see the strong effect that children’s birthdays appeared to have on COVID-19 transmission risk. In counties with the highest prevalence of the disease, a child’s birthday carried more than double the risk of infection of an adult’s birthday, with an increase of 15.8 extra COVID-19 cases per 10,000 people, compared with figures for people who did not have birthdays. While the researchers do not know what accounts for the additional risk, Whaley hypothesizes that perhaps parents are more hesitant to forego a party for a child even in the midst of a pandemic or that party attendees at a child’s birthday may be less disciplined about social distancing.

For both children and adults, though, the findings reflect only the average effect of a birthday on COVID-19 risk, meaning they are almost certainly an underestimate for those who did gather for celebrations over the pandemic. If Whaley and his colleagues had been able to differentiate between people who had a party and those that did not, for example—or between people throwing a party that did or did not wear masks and social distance at that gathering—the results probably would have been even more pronounced.

Even so, the new study clearly confirms that “during a pandemic, it is okay to be a party pooper,” says Donald Redelmeier, a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the research. “It is a big endorsement, in retrospect, of the gains among those who skipped all sorts of social gatherings—weddings, birthday parties, you name it.”

"may" - Google News

June 22, 2021 at 12:40AM

https://ift.tt/3iZPDwu

Children's Birthdays May Have Spread COVID Infections - Scientific American

"may" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3foH8qu

https://ift.tt/2zNW3tO

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Children's Birthdays May Have Spread COVID Infections - Scientific American"

Post a Comment