TOKYO —

Peter and Tina Andrew met in South Africa in the early 1990s, had a short courtship and got married. They shared a desire for travel, for throwing a backpack over their shoulders and a thumb in the air, for drifting on life’s currents, imbibed with wanderlust, unshackled from society’s conventions.

They left South Africa with $500 and figured they’d be gone a year. They were gone seven, hitchhiking and camping, getting odd jobs when they ran out of money, then venturing out somewhere else.

They started in Israel, drawn there by Biblical interests, living on a moshav (communal farm), pruning and packaging flowers. There were trips to Egypt, Jordan and Turkey. On the Greek island of Zakynthos, Tina worked as a bartender and Peter as a water sports instructor. In England, she cleaned toilets and he vacuumed conference rooms at a management college.

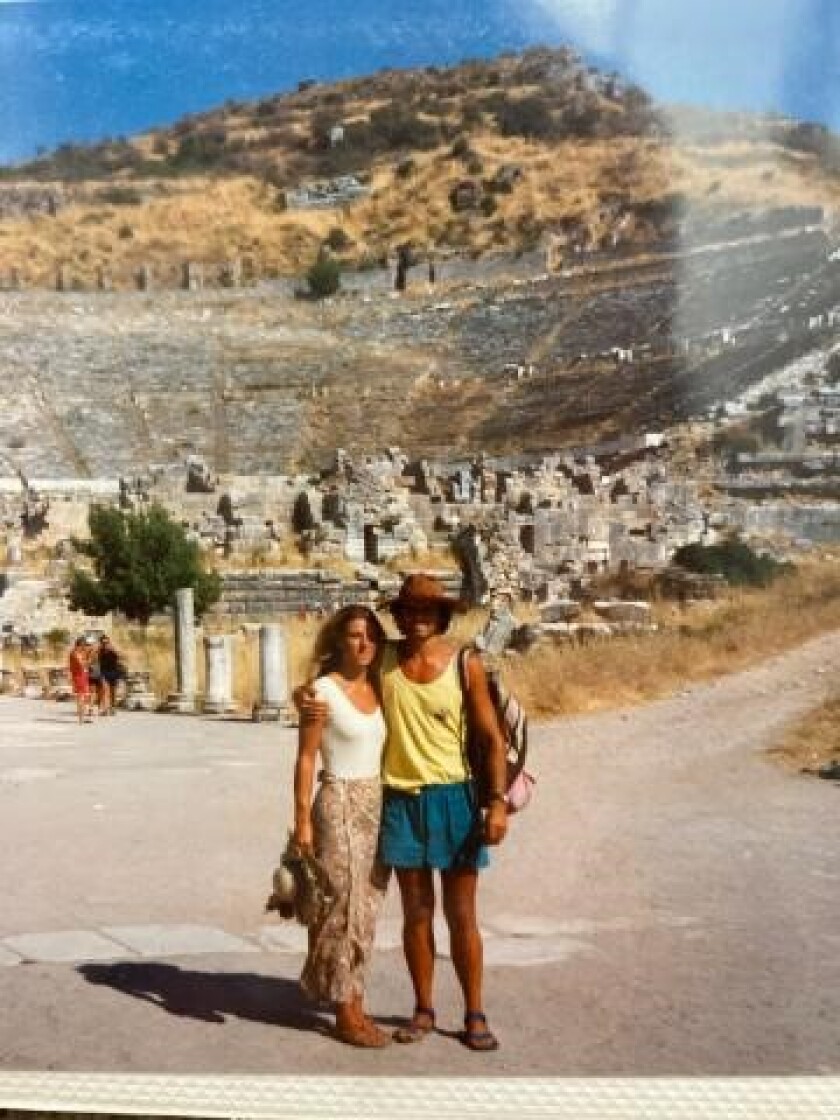

Tina and Peter Andrew, parents of Olympic swimmer Michael Andrew, during their travels to Turkey in the 1990s and the ruins of the Greek amphitheater in Ephesus.

(Tina Andrew)

Their British visas were expiring, and they had purchased a round-the-world airline ticket that started in Hong Kong and visited six continents. Days before the flight, the “Gladiators” TV series — the English version of “American Gladiators,” where contestants compete in various feats of strength and agility — called about Tina’s application and offered her a spot. They went to Birmingham instead, and she filmed a season as a cast member called “Laser.”

Next, they bought an old van in Portugal, wedged a board over the wheelbase to make a bed frame and traced the European coastline. Peter got a metal detector and spent early mornings on empty beaches combing the sand for valuables to buy breakfast, finding coins and the occasional piece of jewelry.

They wouldn’t uncover the biggest treasure of all until a few years later, though, after abandoning plans to take over the family’s vegetable farm in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal region and emigrating to the United States when Peter was hired by a wheat farming company in Aberdeen, S.D. Their 7-year-old son had quickly progressed through swim lessons and was invited to try out for the swim team.

“The very, very first day he went for the tryout, Peter went to pick him up and watched him swim,” Tina says 15 years later. “I’ll never forget the call. Peter said, ‘Drop whatever you’re doing, you need to come and see this.’ Everybody was clinging to the wall for dear life, and Michael’s just swimming across the pool.

“It was like he was in his natural habitat.”

Outside the box

Michael Andrew’s habitat this week is the Tatsumi-no-Mori Seaside Park alongside Tokyo Bay, home of the Olympic swim meet. The 6-foot-6, 22-year-old Encinitas resident is entered in three individual events — the 100-meter breaststroke, 200 individual medley and 50 freestyle — plus a candidate for two relays, with top-5 times in the world this year in all of them, America’s most versatile swimmer in the absence of Michael Phelps and Ryan Lochte.

He’s also America’s most controversial and polarizing and debated swimmer, breaking more than 100 national age-group records, turning pro at 14, forgoing high school and collegiate swimming, being home-schooled since sixth grade and coached by his father, adopting an unorthodox practice regimen with swim sets only a fraction of traditional yardage, not lifting weights, surfing as cross-training, playing chess to hone race strategies, eating a ketogenic diet. And, oh yeah, he has declined to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

Andrew is devoutly Christian and cites Bible verses to describe his stature in the sport. But perhaps a more apt description is his sister Michaela’s favorite quote: “Only dead fish go with the flow.”

He’s definitely a fish. He definitely doesn’t go with the flow.

“We do things differently, not out of spite, not out of, ‘Oh, look at us, we’re trying to defy the odds,’” Andrew says. “We’re always experimenting, we’re always changing things up, we’re always learning as we go. We’ll never at one moment think we have it all figured out. I think that’s one of the pitfalls some elite athletes get into. They think they know it all.

“That’s when you stop improving, when you’re unable to learn from anyone, even if it’s someone below you in terms of ability. I think that’s what has set me a little apart, that we’re not afraid to venture outside the box.”

Or inside a nightclub.

Andrew made the swim team, but Peter, who was a diver in the South African Navy, quickly clashed with the coaches and their training philosophies. Unable to find a suitable club, Peter decided to coach Michael himself. Now all they needed was a pool.

So they purchased an old nightclub in downtown Aberdeen (2021 population: 27,859), tore out the floor and built a four-lane, 25-yard training pool. They did much of the demo themselves, working through the night filling dumpsters with debris while Michael and Michaela slept in the corner. When the building next door was designated for demolition, they bought that, too, and converted it into their home.

Aberdeen Aquaholics, they called their new club. It started modestly, with Michael and Michaela, and grew to two dozen swimmers.

“I think a lot of people don’t believe that a world champion can come out of a little place like Aberdeen,” Peter told a local TV station at the time. “Why shouldn’t they, you know?”

“It was undeniable he had an incredible talent,” says Tina, who serves as Michael’s agent. “The question was: What do we do with that? We believe our children are gifts from God. If God had given Michael that talent, we were here to steward that talent.”

In 2012, they moved to Lawrence, Kan. Bought a house on 10 acres. Built a long shed in the backyard with a training pool inside.

Andrew continued to break age-group records, one after another after another. He grew to 6-feet by age 12 and towered over fellow competitors when he climbed on the blocks. He still holds 15 youth marks in short-course yards or long-course meters; Phelps has nine.

Then he turned pro two years younger than Phelps did and started racing in the World Cups series.

And didn’t win as much.

“It was tough,” says Andrew, who admits he likely would have gone to Texas had he opted to swim collegiately. “A lot of it came from my competition didn’t look the same. When I was young, I was racing kids and there weren’t as many really tough competitors because I grew so quickly and I was stronger and faster. When I got older, I was like, ‘They’re pretty strong as well. They swim fast. Some are focused on single events, so they tend to progress quickly.’

“I finally decided that nobody else determines my worth or value based on my performance. I needed to kind of take control of that mentally and understand I worked so hard that I might as well stand up confidently.”

The move to Encinitas in 2018 seems to have helped as well, immersed in a health-conscious, Olympic-literate community (70 other athletes with San Diego ties are in Tokyo), connected with the ocean’s therapeutic vibe and California’s openminded ethos.

The family actually moved because of Michaela. With Michael in Europe to race and train, Tina and Peter asked their daughter how she wanted to celebrate her birthday. She wanted to take a trip up the California coast in a van, stopping at all the best surf spots. Encinitas was on the itinerary.

On the drive home, it hit Tina: This is where they needed to be.

“We couldn’t,” she says, “bring the waves to Kansas.”

Quality, not quantity

The 2009 American Swimming Coaches Association convention was held at the Marriott Harbor Beach hotel in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. One of the speakers was Brent Rushall, a professor emeritus from Australia in San Diego State’s School of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences.

“This presentation is deliberately controversial,” Rushall told the audience, “and I make no apology for that.”

He was presenting a paper titled, “The Future of Swimming: Myths and Science,” that debunked conventional wisdom in conditioning, altitude training, lactic acid, stretching, whole arm propulsion and pacing. Or put another way: He was saying everything American swim coaches had been doing for decades was wrong.

Listening intently that day was a former naval diver from South Africa who a year earlier had built a pool in a nightclub in Aberdeen, S.D., so he could train his gifted and growing son. Peter Andrew introduced himself to Rushall afterward. They needed to talk.

What interested Peter most was Rushall’s theories on training. Rushall is the father of Ultra Short Race Pace Training, or USRPT, the idea that you practice in quick bursts at top speed instead of the longer, shorter swim sets that were, and still are, the norm.

“His mother and father sensed that if you wanted to swim fast, you’ve got to swim fast,” says Rushall, now 81. “The more you can swim fast, the better you’ll be.”

Rushall has been involved in the sport since 1957 and worked with some of its coaching icons: Forbes Carlile, Doc Counsilman, George Haines. What really got him thinking, though, was a trip to San Jose State in the late 1960s to observe a training session with Lee Evans, the 1968 Olympic gold medalist and world-record holder at 400 meters — running, not swimming.

Evans’ workout: He ran 200-meter repeats at a blazing 20.4 seconds.

“Those things kind of stick in your mind,” Rushall says. “You don’t get the top 400-meter runners running at 5,000-meter pace. You get a lot of that in swimming. Man is a creature of habit, and the habits that he does, that’s what he becomes. It was being done in other sports but not in swimming.

“The problem with swim coaches is very few of them have coached any other sport. If you had a good swimmer, it was automatically assumed you were a good coach and they would make up excuses why their swimmer swam well. A lot of it was just invented folly.”

The South African farmer and Australian professor began communicating regularly, and soon Michael was training in short, quick bursts instead of endless slogs staring at the black line on the bottom of the pool. They rarely use what Rushall calls “toys,” training aids like hand paddles and flippers and pull buoys that he insist do more harm than good.

A typical workout: 25-meter sets of 20 at race pace with 15 seconds of rest. You try to complete the set but stop when you hit a pre-established “fail” time, because going any slower reaches a point of diminishing returns.

The sessions themselves are short, usually less than an hour including warm-up. He’ll go home and rest, then return to the pool in the afternoon for another.

Michael Andrew competes in the preliminary heats of the 100 breaststroke at the Tokyo Olympics on Saturday.

(Getty Images)

“The focus is always specificity,” Andrew says. “The way our brain works, we code movements. In order for us to swim faster on race day, we want to make sure we’re swimming fast in every session so that it just happens subconsciously. I’m basically simulating the pain, the pace, the technique, the efficiency that I have to hold when I’m dying in that race or when I’m fresh at the beginning of that race.”

Andrew doesn’t lift weights, either. (Rushall is fond of saying, “Weights don’t float.”)

“It shortens the muscle and you become bulky, and it isn’t the most efficient way to move through water,” Andrew explains. “For me, I have to be so fresh when I swim that if I’m lifting and fatiguing my body, I’m unable to hold pace and I start coding the wrong movements, essentially. If it’s not really aiding the goal of swimming faster and swimming smarter, then why waste time doing it?”

The swimming establishment shook its head.

John Leonard, the executive director of ASCA, wrote in a 2014 email to his Board of Directors that “the USRPT nonsense had no coherent background in terms of training young athletes … but it had a lot of appeal to young coaches (and athletes) who are not knowledgeable about the history of training in the world and were being hoodwinked into thinking this is something new … when in fact of course it is a failed methodology.”

Except not with Andrew. Not now. Vindication and validation came at the U.S. Trials last month in Omaha, Neb., where he qualified for more events (seven) than any other man and became the first American ever to make the team in the breaststroke, which uses different sets of muscles than the other three strokes, and another single-stroke individual event (50 free, in his case).

He enters Tokyo with the fastest time in the world this year in the 200 IM (1:55.26), third in the 100 breast (58.14) and fourth in the 50 free (21.48). He’s also fourth in the 100 butterfly but scratched that event at the trials because it conflicted with another.

“Obviously, it’s all tied to results,” Andrew says. “If I didn’t make the team, then everybody would feel justified in saying, ‘We called it. We know Michael is yada, yada, yada.’ It’s sad, because I see a lot of athletes who can crumble under that negative criticism because it’s so hard to turn a blind eye because it’s just everywhere.

“I’ve never tried to go out of my way to prove people wrong. The stuff that I allow into my head I use as fuel, but the majority of it I ignore.”

Passing the torch

Lochte is the world-record holder in the 200 IM at 1:54.00 in 2011. Next on the all-time list is Phelps.

Next is Andrew, with his 1:55.26 from the semifinals in Omaha. He ripped off a blistering butterfly opening leg and was still under world-record pace after 150 meters before fading. Only one other person is within a second of him this year, Great Britain’s Duncan Scott, and he’s .64 slower.

Andrew won the final by 1.53 seconds. Lochte, in a bid to make a fifth Olympic team at age 36, was seventh, four-plus seconds behind.

Lochte climbed out of the pool, walked down the deck and hugged Andrew. And leaned into ear and whispered something.

“He told me he’s passing the torch to me,” Andrew says. “For him to say, ‘Hey, you’re the guy now. Go kick some butt,’ that’s a huge honor. It was pretty epic.”

"flow" - Google News

July 26, 2021 at 01:24AM

https://ift.tt/3eWMnPz

Encinitas Olympic swimmer Michael Andrew goes against the flow - Encinitas Advocate

"flow" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Sw6Z5O

https://ift.tt/2zNW3tO

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Encinitas Olympic swimmer Michael Andrew goes against the flow - Encinitas Advocate"

Post a Comment