When epidemiologist Chikwe Ihekweazu posted a blog in 2010 warning that his home country of Nigeria would “pay the price the hard way” if a pandemic struck, he never imagined that the government would not only ask for his advice, but also his leadership. In 2016, he was tasked with leading the nascent Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), where he would increase the agency’s staff numbers and laboratory capacity, and navigate the country through waves of infectious disease outbreaks.

These accomplishments — including his guidance during the COVID-19 pandemic — caught the attention of the World Health Organization (WHO), which announced earlier this month that Ihekweazu would lead its new Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence in Berlin. Details about the hub, which will initially be funded by the German government, are scant, but the WHO has cast it as an initiative to better gather data on infectious diseases from around the world and assess them so that authorities can make rapid, informed decisions in public-health emergencies.

When Nature profiled Ihekweazu a few years ago, we recognized his importance for pandemic preparedness, highlighting both his leadership skills and the need for them in countries such as Nigeria that face frequent deadly outbreaks. In truth, no one individual can stop a pandemic. Ihekweazu understands this, which is why he’s devoted his career to strengthening the connections between people running public-health systems. Doing so at the global level will be his biggest challenge yet.

Nature spoke with Ihekweazu about his exit from the NCDC and his hopes and fears for the WHO hub.

Will it be difficult for you to leave the NCDC for this new opportunity?

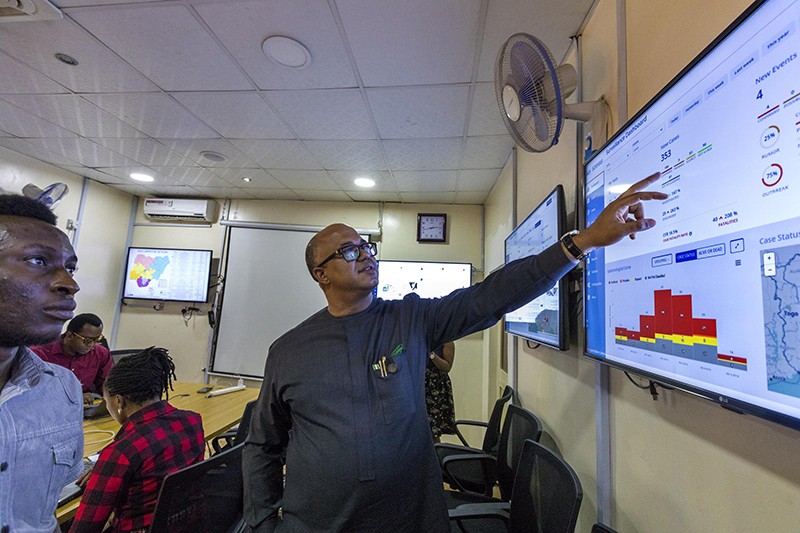

It’s very hard. It’s been much more than a job for me. We’ve made so much progress and grown a lot. We now have about 700 people working with us. The supply chain is working and the labs are working. We have two emergency operation centres running in parallel for cholera and COVID-19, and surveillance teams that detect incidents and respond. And, for the first time, the threat of emerging infectious diseases is no longer hypothetical, so our political leadership — to some extent — recognizes the importance of the work that we do. We have the building blocks to take us into the future, which is why I think it’s OK for me to let someone else take the NCDC to the next stage.

Having said that, I didn’t want to let go just yet. It took something as important as the WHO hub to pull me away.

What attracted you to the WHO hub?

The DG [director-general of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus] called me and said, “Listen, I am constantly thinking of how to make this organization work better, and thinking of how to learn lessons from the pandemic while we are still in the pandemic. We need to keep responding, but at the same time I want to set up a group that will think about how to better gather information so that the organization can make better decisions.”

That call inspired me. If the DG had proposed a hub just to do fancy data analysis, I wouldn’t have been interested because I don’t think that would address the biggest problems we have — and it’s not my strength.

What are the biggest problems you hope to fix — and why do you want to solve them at the WHO?

I want to make the mechanics of reporting disease-related information easier, and also demonstrate that the WHO can use that data to help countries that share it. One way to do that is to enable countries to derive value from their own data.

I wouldn’t want to do this at a venue other than the WHO. I know that different countries are creating hubs, as are some big donors. They may be able to analyse publicly available data, but they won’t have the same access to information from countries that the WHO does. Speaking as the current director of the Nigeria CDC, I can tell you that I wouldn’t share my data openly with a hub located in another country. We share our data with the WHO without worry because the WHO belongs to us and other countries as a member-state organization, and has a mandate from countries to monitor health risks and coordinate the response in health emergencies.

How will the WHO hub operate?

I’ll know more details in November or December. But one major plan is to harness collaborative intelligence. Our expected capacity is 120 researchers, but a good proportion of them won’t be from the WHO. They will visit for intervals, like six months or one year, to look intensively at specific issues. That will give the organization the opportunity to bring in smart people with specific expertise, and it will allow smart people who want to spend some time with the WHO to come into the organization without feeling obliged to move permanently to Berlin or the WHO headquarters in Geneva [Switzerland]. This is how we’re attempting to enable the cross-fertilization of ideas that we hope leads to greater insights around infectious disease threats.

What are your concerns regarding the hub?

My source of anxiety is that expectations are so high that people will expect us to demonstrate results immediately — to, you know, identify a single case of a new virus anywhere in the world and stop it. And that’s not really what we are setting out to do. We will offer our leadership, knowledge, systems for data sharing and analytics to help countries be more confident in the decisions they have to make. But the decisions they make are their own.

One of the biggest challenges we have globally is that it’s very difficult to ensure that decisions are made in an equitable way. For example, we can determine that the most effective way of protecting the whole world is by vaccinating a particular proportion of people in every country, but a few countries that are rich and powerful may decide to do things differently. So I think we also have to be realistic in saying that the WHO can provide better data, and better analytics and advice for political leaders, but ultimately it is up to them to make good decisions. And it’s up to the electorate to elect leaders who care about this pandemic.

We all have to work together to deliver the future we want.

How does it feel to leave Nigeria during the COVID-19 pandemic?

I will leave Nigeria physically for now, but Nigeria is always in my heart. I am always thinking about how to make Nigeria better, and how to make the continent work better. There’s a lot of talk right now about local vaccine manufacturing in Africa, but I think we need to go way beyond that. We need to inspire a whole new generation of young people to do science, and we need to attract Africans that are working in universities around the world to come back to the continent and help build up capacity. The WHO hub is my next assignment — and I believe that I can do a lot of good for the continent from there — but together with many other Africans, I am focused on the long game. We want to make sure that we are better prepared for the next pandemic, and that we aren’t just participants in the consumption of vaccines and other technologies, but are also participants in the basic science and research that leads to them.

"flow" - Google News

September 22, 2021 at 05:20AM

https://ift.tt/3lP5ldh

Leader of WHO's new pandemic hub: improve data flow to extinguish outbreaks - Nature.com

"flow" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Sw6Z5O

https://ift.tt/2zNW3tO

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Leader of WHO's new pandemic hub: improve data flow to extinguish outbreaks - Nature.com"

Post a Comment